Anonymous social networking

Secrets and lies

SOCIAL media may have brought millions of people together, but it has torn many others apart. Once, bullies taunted their victims in the playground; today they use smartphones to do so from afar. Media reports of “Facebook suicides” caused by cyberbullying are all too common. Character assassination on Twitter is rife, as are malicious e-mails, texts and other forms of e-torment. A recent review of the academic literature on cyberbullying suggests—conservatively—that at least a quarter of school-age children are involved as either victim or perpetrator.

A new generation of smartphone apps is unlikely to help. With names like Whisper, Secret, Wut, Yik Yak, Confide and Sneeky, they enable users to send anonymous messages, images or both to “friends” who also use the apps. Some of the messages “self-destruct” after delivery; some live on. But at their heart is anonymity. If you are bullied via Facebook, Twitter or text, you can usually identify your attacker. As a victim of an anonymous messaging app you cannot: at best you can only guess which “friend” whispered to the online world that you might be pregnant. As the authors of the paper cited above point out, anonymity frees people “from traditionally constraining pressures of society, conscience, morality and ethics to behave in a normative manner.”

Unsurprisingly, none of this is deterring venture-capitalists. Whisper, which was launched last November, has raised more than $20m from blue-chip funds such as Sequoia Capital. Secret, at less than two months’ old, recently scored almost $9m from a group that includes Google Ventures, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, and actor Ashton Kutcher’s A-Grade Investments.

Not every venture capitalist is as sanguine about investing in what have been dubbed “bullying apps”. In a 12-tweet diatribe, Marc Andreessen, who co-founded Netscape and is now a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, a hot Silicon Valley VC firm, took issue with both the apps and those investing in them. “As designers, investors, commentators, we need to seriously ask ourselves whether some of these systems are legitimate and worthy,” he wrote; “… not from an investment return point of view, but from an ethical and moral point of view.” Mark Suster, another well-known investor, took a similar stance on his blog: “It’s gossip. Slander. Hateful. Hurtful. It’s everything [Silicon] Valley claims to hate about LA but seemingly are falling over themselves at cocktail parties to check 5 times a night. We can do better.”

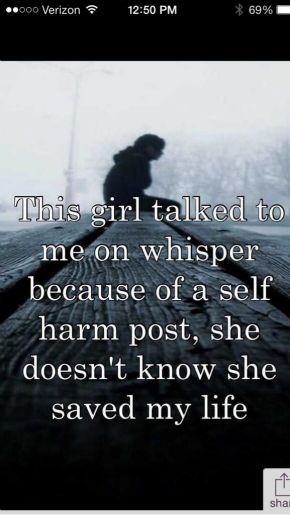

This is not, of course, how the startups’ creators see things—and in fairness many of the secrets they share are harmlessly banal. David Byttow, co-founder of Secret, has claimed his app assists people in “voicing their opinion in a very constructive way.” Michael Heyward, Whisper’s boss, took to Twitter to defend his app against Mr Andreessen, tweeting a screenshot (pictured above) of a whisper that read “This girl talked to me on whisper because of a self harm post, she doesn’t know she saved my life.” (This was shortly after he hired Neetzan Zimmerman, formerly of celebrity-smearing site Gawker, as its editor-in-chief, and Whisper began whispering about the alleged infidelity of a well-known actress.)

The app companies claim they have or are working on ways to deter slanderous or abusive posts. Secret says it removes such posts, although that rarely seems to happen quickly or consistently. And after hosting posts that have included multiple shooting and bomb threats—some of which led to school evacuations—Yik Yak is now using “geofencing” technology to prevent its app being used at a majority of America’s middle and high schools. That will do little, however, to affect its use outside school hours or at universities, which Yik Yak is still targeting.

The startups’ bigger challenge may be figuring out a business model. Advertising will be a hard sell: most of the services collect little or no data about their users besides location, and their unpredictable demographic ranges from tweens to thirtysomethings. Few advertisers will want to be associated with apps that count bomb threats and cyberbullying among their core services. And teens—the services’ most intensive users—are notoriously fickle in their app appetites. Once they realize that few people care about their secrets—at least compared with those of famous actresses—they will move on.

The market for such services is also littered with failures. Formspring, an anonymous Q&A site beset with cyberbullying and allegations of related suicides, raised $14m before shutting down a year ago. It has since been reincarnated, at least in spirit, as spring.me. Latvia-based Ask.fm, a Formspring rival that had won a few big advertisers, lost many of them after it too was linked to cyberbullying and multiple suicides. (Among those to quit was British tabloid The Sun, which shows just how bad things were.) Juicy Campus lasted 18 months before shutting down in 2009 amid similar controversies—and after venture-capital firms realized it would never turn a profit.

And then there is the original secrets website, PostSecret, which launched in 2005. In September 2011 it decided to join the smartphone age with an app for Apple’s iPhone. After trying and failing to weed out offensive secrets from the millions posted, PostSecret scrapped the app four months later, never to return. A pile of venture-capital cash may be about to suffer the same fate.

(http://www.economist.com/blogs/schumpeter/2014/03/anonymous-social-networking)

No comments:

Post a Comment